Story by Ari Shapiro/NPR

A group of men with full glasses proudly pose with

their keg of beer in San Francisco, 1895.

If you crack open a beer this Fourth of July,

history might not be the first thing on your mind. But for Theresa McCulla, the

first brewing historian at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American

History, the story of beer is the story of America.

"If you want to talk about the history of

immigration in America, or urbanization or the expansion of transportation

networks, really any subject that you want to explore, you can talk about it

through beer," McCulla says.

Since taking the job earlier this year, she has

combed through the Smithsonian's archives and pulled out treasures that show

beer's part in American history — whether that has to do with advertising,

technology, gender roles or even popular entertainment.

Pointing to some sheet music in the collection for a

song called "Budweiser Is a Friend of Mine," she explains that the

tune premiered on Broadway at the Ziegfeld Follies in 1907.

National Museum of American History, Archives Center

"The lyrics of the song tell the story of a man

who goes out drinking in a bar and sings about how he prefers his Budweiser to

his wife, because his beer does not talk back to him," McCulla says.

"But the song concludes with his wife pouring him a schooner of Budweiser

at home so he does not need to drink elsewhere."

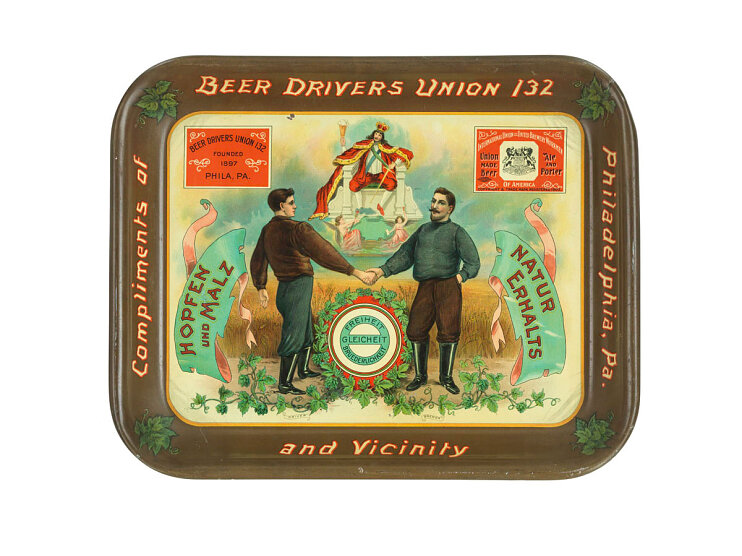

You can't truly tell the American story of beer,

though, without talking about immigration. More than 1 million German

immigrants came to the U.S. in the second half of the 1800s — and they were

beer drinkers.

"They brought new kinds of brewing yeast, they

brought different kinds of brewing methods, and suddenly they produced this

lager beer — a very light, crisp brew that became very popular with Americans,"

McCulla says.

Those immigrants transformed the kind of beer

Americans drink and established a new industry in the process. The drink

evolved from heavy, English-style ales to the cold, quaffable style that's

common today. And instead of homebrews, by 1900 many cities had entire

neighborhoods full of breweries.

McCulla says one of the most interesting aspects of

the story of American beer is that it has come full circle: from the early days

of homebrews to mass-produced beer, through the crash of Prohibition and back

to a resurgence of microbreweries.

"We now have so many breweries in this country,

we have exceeded the pre-Prohibition number of breweries," McCulla says.

"We have reached over 5,000 breweries at this point, so it's truly the

golden age to be a beer drinker."

Not far from the Smithsonian, this entire cycle is

happening in one place. Outside the Portner Brewhouse in Alexandria, Va., a

sign says: "Established 1869, Re-Established 2012." The company was

founded by Robert Portner, a German immigrant. At its peak, the company was the

biggest employer in the city. More than 600 people worked for Portner, churning

out more than 6 million bottles of beer every year.

Portner's company was forced to close during

Prohibition in 1916. But a century later, sisters Catherine and Margaret

Portner, two of his great-great-granddaughters, reopened the brewery just a few

miles from its original site.

Some of the company's early marketing materials are

in the Smithsonian's collection. The original advertisements note Robert

Portner's company as the original king of beers, says Catherine Portner — long

before Budweiser began using that phrase.

Sisters Catherine (left) and Margaret Portner have

re-established Portner's Brewery, which was opened in Alexandria, Va., in 1869

by their great-great-grandfather, then closed during Prohibition.

Historical artifacts line the walls of the Portner

Brewhouse, and the kitchen serves up food with a German twist. And at the

in-house brewery, the sisters have re-created some of the original Portner's

brews, based on the notes that Robert Portner wrote in German. But they have

also made some innovations themselves.

And, harking back to the early days of homebrewing,

the company also has a "Craft Beer Test Kitchen Series," which gives

homebrewers professional experience and feedback on their original recipes,

which are brewed at Portner's and then sold to thirsty customers.

Catherine Portner pours a cloudy yellow beer from

the tap. "This is the Hofbrau Pilsner that we have reconstructed from the

Robert Portner brewing company," she says. The Pilsner was one of the

company's flagship beers.

It doesn't look or taste like a glass full of

American history, or technology or immigration — even though on some level, it

is all of those things. It just tastes like a really good beer.