For home cooks,

widespread techniques for judging doneness of chicken may not ensure that

pathogens are reduced to safe levels. Solveig Langsrud of the Norwegian

Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research and colleagues present

these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on April 29, 2020.

Chicken can harbor the

bacterial pathogens Salmonella and Campylobacter. High temperatures can kill

these microbes, but enough may survive to cause illness if meat is undercooked.

Recommendations for monitoring doneness vary widely, and the prevalence and safety

of methods commonly used by home cooks have been unclear.

To help clarify

consumers' chicken cooking practices, Lansgrud and colleagues surveyed 3,969

private households across five European countries (France, Norway, Portugal,

Romania, and the U.K.) on their personal chicken cooking practices. They also

interviewed and observed chicken cooking practices in 75 additional households

in the same countries.

The analysis indicated

that checking the inner color of chicken meat is a popular way to judge doneness,

used by half of households. Other common methods include examining meat texture

or juice color. However, the researchers also conducted laboratory experiments

to test various techniques for judging doneness, and these demonstrated that

color and texture are not reliable indicators of safety on their own: for

example, the inner color of chicken changes at a temperature too low to

sufficiently inactivate pathogens.

Food safety messages

often recommend use of thermometers to judge doneness, but the researchers

found that the surface of chicken meat may still harbor live pathogens after

the inside is cooked sufficiently. Furthermore, thermometers are not widely

used; only one of the 75 observed households employed one.

These findings suggest a

need for updated recommendations that guarantee safety while accounting for

consumers' habits and desire to avoid overcooked chicken. For now, the

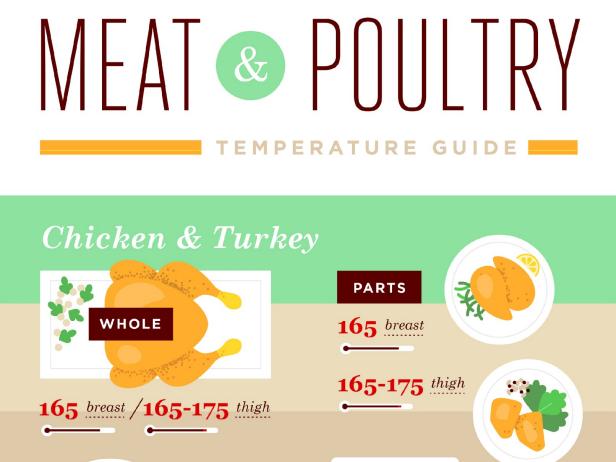

researchers recommend focusing on the color and texture of the thickest part of

the meat, as well as ensuring that all surfaces reach sufficient temperatures.

"Consumers are often

advised to use a food thermometer or check that the juices run clear to make

sure that the chicken is cooked safely -- we were surprised to find that these

recommendations are not safe, not based on scientific evidence and rarely used

by consumers," adds Dr Langsrud. "Primarily, consumers should check

that all surfaces of the meat are cooked, as most bacteria are present on the

surface. Secondly, they should check the core. When the core meat is fibrous

and not glossy, it has reached a safe temperature.

Story Source:

Materials provided by

PLOS. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.